Uninstalling the Malware of Bureaucracy

“...We need to take on the apologists. Though few executives admit to being fans of bureaucracy, fewer still seem genuinely committed to killing it.” - Gary Hamel

1. The Bureaucratic Elephant in the Room

Like many people in tech today, I’d like to see the transformation conversation rise above ground level discussions of tools, t-shirts and “spotify models”. As consultants, we politely graze the symptoms when we evangelise about changing “cultures” and adopting a “devops mindset”. But bureaucracy - the multi-tiered elephant in the room that’s butchering productivity and costing us trillions of dollars globally - is rarely called out in this context.

Today, we simultaneously co-inhabit two conflicting ideological eras. On the one hand, in the world of “bits”, we are embracing complexity head on, building ever more interconnected, distributed and resilient systems and champion speed and agility. On the other hand, in the world of organisational structures, we’re still comfortably operating in monolithic bureaucratic hierarchical structures (that date back to the early 1900's) and label our people as “resources” (in fact, there’s a whole department named after that in most organisations).

Bureaucrats are heavily attracted to the illusion of certainty, pursuing standard, quantifiable cost-cutting ‘efficiencies’ without considering delayed or hidden costs such as driving out good people, stifling innovation and hampering decision-making. But decentralisation and resilience-building principles that have been used by software engineering for more than 20 years may hold the answer for boosting productivity, treating chronic stagnation and creating game changing innovation.

The Global Productivity Problem

Productivity slowdown is a global problem. In recent years, both the IMF and OECD pointed out that global productivity fell sharply following the GFC and has remained sluggish since, adding to a slowdown already in train before. The Australian economy went into the COVID-19 pandemic with weak growth in both productivity and average incomes. In 2018-19, Australia’s labour and multifactor productivity went backwards, while growth in per capita income slowed to just 0.3%. Suppressing the pandemic will come at a large cost to economic activity with Australia heading into its deepest downturn in almost 100 years. As any economist will tell you, productivity growth is the key driver of prosperity. When productivity increases, so do incomes and living standards. Slow productivity growth can create economic and social instability.

Like many in the industry, I’m a believer in the “continuous improvement” ethos that inspired the “DevOps” approach to problem solving. These grass-roots movements were intended to unlock productivity and empower engineers to improve their own work environments and deliver more economic value. As tactical approaches, they are undoubtedly valid constructs for supporting agility, collaboration and innovation. But the root of the so-called “productivity problem”, both in the tech space and, more broadly, in today’s global economies and organisations, lies in a dated technology that is sadly still holding us hostage today: bureaucracy.

The Bureaucracy Tax

Prof. Gary Hamel, a Harvard Business School Professor who’s been writing about the dreaded “B word” since the 90’s, makes a powerful point in his 2016 paper “The $3 Trillion Prize for Busting Bureaucracy (and how to claim it)“:

“...like all technologies, bureaucracy is a product of its time. In the century and a half since its invention, much has changed. Today’s employees are skilled, not illiterate. Communication is instantaneous rather than tortuous; and the pace of change is exponential rather than glacial. Nevertheless, the foundations of management are still cemented in bureaucracy.”

Prof. Hamel estimates the true cost of excess bureaucracy northwards of US$3 trillion annually (approximately 17% of the US’s GDP). In Australia, the Institute of Public Affairs (IPA) estimates that red tape and government bureaucracy alone is costing the taxpayer $176bn and 10% of GDP in 2019. As Prof. Hamel writes “...Band-Aids, braces and bariatric surgery don’t fix genetic disorders”. “Bureaucracy must die”. To address the global problem of sluggish productivity, we need to start by scrutinising the architecture and ideology of modern management.

The Problem With Bureaucracy Today

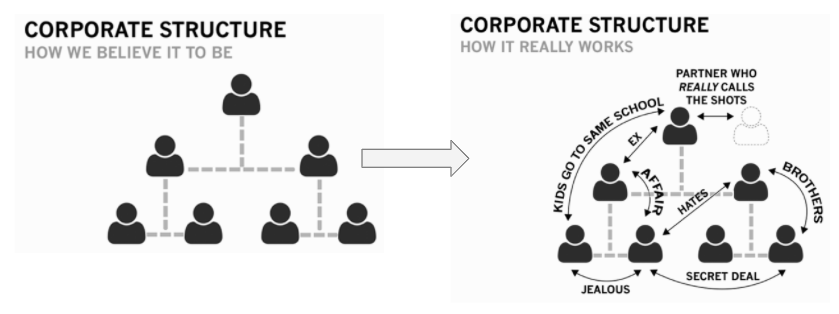

“.....bureaucracy is a massive, multi-player game. It’s the field upon which millions of human beings compete for status and wealth. As in all games, some skills are more germane than others. While expertise and execution count for much in bureaucracies, other skills are often even more valuable: deflecting blame, defending turf, managing up, hoarding resources, trading favors, negotiating targets and avoiding scrutiny.”

- Gary Hamel

Source: Brian J. Robertson’s Holacracy - The Revolutionary Management system that abolishes hierarchy

No organisation methodology or design is perfect. As Prof. Hamel notes, bureaucracy is both widely popular and tricky to eradicate because it seemingly works. It facilitates efficiency at scale by introducing clear processes, procedures and lines of authority, specialised divisions and standardised tasks. It’s consistently applied across industries and geographies, which makes it seem familiar and reliable. And just like an autocratic regime, it’s well entrenched, accepted as norm and defended by those who benefit from it.

But many business leaders and leading academics today recognise that bureaucracy is a “tax on human achievement”. CEOs, from Walmart’s to JP Morgan’s singled out bureaucracy as a “villain” and a “disease” that “drives out good people, slows down decision making, kills innovation and is often the petri dish of bad politics.” Interestingly, criticisms of bureaucracy made back in the 70s still seem on point today. Anyone who's ever worked in today’s typical bureaucratic organisations will be familiar with the following product design features:

- Rigid hierarchy - Top-down limited information flows where experience and the past are overvalued and new thinking is undervalued. Promotions are political rather than meritocratic. Questioning is discouraged. Conformism and sycophants are rewarded.

- Power struggles, fiefdoms & conflicting interests - A top heavy, complex structure where power struggles are inevitable and indeed encouraged. The boundaries of authority and responsibility overlap prompting people to maximize their own advantage.

- Narrow authority & lack of ownership - Multiple approval layers and convoluted processes preventing any one person from owning and delivering an outcome as they cannot traverse functional lines without “explicit formal agreements” and endless meetings and red tape. CEOs feel the hefty burden of management, becoming a single point of failure for all decisions and sign-offs. Meanwhile, narrow individual authority leads to lack of accountability and shrinks the incentives to innovate and contribute.

- Over staffing & excessive overheads - Overstaffing due to empire building and excessive layering leads to a cumbersome and costly system that is slow to respond to challenges and expensive to run.

- Lack of productivity - Aka “navel gazing” - considerable interdependence of people and tasks leads to an absorption in internal relations at the expense of paying attention to the world outside the organisation, particularly to clients.

- Cumbersome decision making - All business decisions are made by large and slow moving groups without regard to expertise or relevance. To make decisions in other ways is considered illegitimate and not in the spirit of ‘matrix’ operations.

2. From Central Command to Distributed Decision Making

How We Got to the Matrix

Centralisation was a key feature of military organisation for centuries. Unwilling, often poorly educated conscriptees needed to be tightly controlled by the officer class to deliver predictable mission outcomes during war. The centrally controlled (and reliably tragic) trench warfare tactics in WWI heavily satirised in the BBC’s “Blackadder Goes forth” provide some insight into the centralisation fallacy.

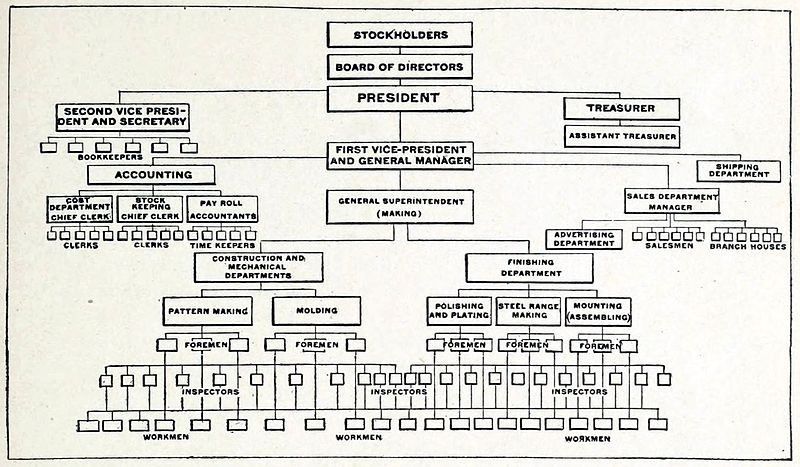

The quintessential hierarchical pyramid with a “command and control” structure is a key feature of many large and small organisations today, even though it is based on 100 year old management theory called “Taylorism” (named after the industrialist management consultant Frederick Taylor). Taylor’s military-born top-down, rigidly predetermined, “scientific management” philosophy - premised on a belief in a "one best way" to get work done - heavily influenced American industrial culture in the 1890’s and optimised productivity, particularly in the steel industry. Humans were seen as fundamentally lazy, in need of financial incentives and close monitoring in order to do work. Taylorism’s fans included the likes of Lenin and Stalin, who were eager to apply his “stopwatch wielding” management approaches within the Soviet Union.

Taylor’s model laid the foundation of contemporary management structures - a combination of specialized vertical columns (departments or divisions) and horizontal tiers representing levels of authority, with the most powerful literally on top - the only tier that can access all columns. The leadership class envision strategic decision making while the workers provide the manual labour and follow instruction.

Chart of a large Company Manufacturing Stoves, 1914

In the 70s, a new organisation form called the ‘matrix’ evolved to deal with the increasing complexity and ambiguity of projects. Matrix organisations were identified by dual chains of command where employees essentially had two bosses and dual responsibilities as part of horizontal and vertical team structures. Companies in the aerospace, banking, packaged goods and professional services industries and government agencies adopted the matrix model in various configurations since. The matrix model was intended to facilitate a rapid management response to changing market and technical requirements. The trouble was it didn’t live up to its promise and was criticized for being complex, frustrating and fraught with issues such as anarchy, power struggles, severe groupitis, collapse during economic crunch, excessive overhead, uncontrolled layering, navel gazing, and decision strangulation. Despite all that, the Tayloristic “matrix” model (or some version of it) with all its ills is still the most common organisational template for the businesses we work in today.

Military Decentralisation in Action

Helmuth von Moltke, the famed Prussian general and tactical genius, famously coined the phrase “no plan survives contact with the enemy”. Sometime in the 1860’s, Moltke realised that the growing size of armies, combined with the speed and complexity of war, made it impossible to predict and maintain a centralised command model. Moltke introduced radical new ideas which revolutionised war fighting. His idea of “Auftragstaktik” (“mission command” in German) or more accurately “leading by mission”, stood for disseminating the higher level, mission-based, strategic goals to well-trained officers who were operating on the front. The idea was to rapidly distribute decision making authority to those who would have the flexibility and independence to make right tactical decisions at the right time, without the need to consult central commanders.

This decentralised decision making approach yielded a decade of Prussian military victories and reemerged in WWII as the underpinning principle of the famous German blitzkrieg (aka “lightning warfare”). The Germans under Rommel’s command famously surprised, wrong footed and encircled their opponents through speed via dynamic integration of tanks, dive bombers, motorised artillery and troops empowered by decentralised command.

In the 20th century, a kinetic decentralised approach has become a key first principle of military doctrine, particularly within the special forces and counterterrorism communities to address the speed and complexity of war. This tactic was famously employed by the Israeli Defence Forces who were outnumbered and surrounded during the 1967 Six Day War. Israeli forces managed to secure an astounding and unprecedented victory in six days, defeating Egypt, Jordan and Syria through a swift, aggressive and distributed attack.

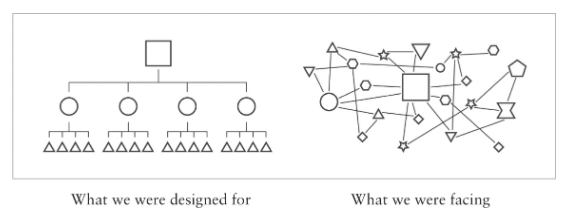

Team of Teams

In 2015, former US Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) commander, General Stanley McCrystal, penned “Team of Teams - New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World”. In the book, McCrystal traces his journey to transform his organisation and leadership when facing Al Qaeda in Iraq and Afghanistan in the early 2000’s. He realised the enemy’s “nonlinear” unpredictability was fundamentally incompatible with reductionist managerial models based around planning and prediction. This new chaotic environment required a different approach.

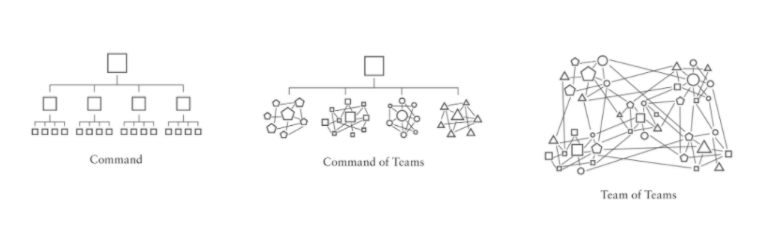

Source: McCrystal: “Team of Teams - New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World” (2015).

Many of the challenges McCrystal faced are identical to challenges beleaguering large organisations today - lack of trust, bureaucratic inertia, conflicts of interests and disconnection from mission objectives. One of McCrystal’s key insights was that his command needed to transform to mirror the problem space: an elusive, fluid, largely decentralised and self-directing network-like enemy that ”was not efficient but was adaptable—a network that, unlike the structure of our command, could squeeze itself down, spread itself out, and ooze into any necessary shape”.

McCrystal realised that while he had an “awesome machine” - an efficient “Taloristic” military assembly line - it was too slow, too static, and too specialised - too ‘efficient’ - to deal with the volatility his team encountered. His Task Force reviewed their own method of operation, including strategy, structure, process, and most importantly information sharing culture. They realised they had to be more adaptable and overhaul the traditional military “need to know” communication model to promote rapid information sharing (“joint cognition”) in order to deliver the right intelligence to the right teams so it could be acted upon in near real-time.

The NASA Angle

In his book, McCrystal cites George Mueller’s famous “systems management” overhaul of NASA’s 1960’s Apollo program (~300,000 individuals worked for 20,000 contractors and 200 universities in 80 countries) to meet President Kennedy’s goal to put a man on the moon before the end of the decade. Mueller pioneered concepts of neural information sharing networks. “All data were on display in a central control room that had links with automated displays to Apollo field centers.” In an era before instant messaging, Mueller had pushed to engineer a complex series of hundreds of radio channels to achieve an unprecedented focus on information sharing. As one engineer described, “You could tune into North American 2, and you’d be listening to the guys working the engine. If there was a problem there, you could hear how they were handling the problem.”

Source: McCrystal: “Team of Teams - New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World” (2015).

New Rules of Engagement

McCrystal transformed his Task Force from a command and control structure to a network-like model he calls “team of teams” that favoured adaptive and emergent “group intelligence”. He highlights the need to create:

- A common purpose - aligning competing agendas and killing silos.

- Shared consciousness - open and rapid communication shared in constant conversation with the team.

- Empowered execution - distributing authority, allowing teams and individuals to act quickly and independently on the information they have.

- Trust building - pushing leadership down and providing the team with increasing levels of control, trust and responsibility.

- Cross-pollination of teams - using short inter-team secondments to promote trust, relationships and eliminate silos obstructing proactive information sharing.

- Gardener leaders over heroic leaders - focussing on leaders who develop shared consciousness and development of others across the wider organisation over single “command & control” decision makers or tribalistic personalities.

3. Decentralisation in Tech

Agile, Chaos Monkeys & Open Source

Over the past 25 years, decentralised decision making has been at the core of how we make software. Originally started in 2001 as a reaction to the slow, bureaucratic and stifled creativity experienced in traditional waterfall methods of software development, the Agile approach and methodologies have revolutionised the way software is developed. Today, Agile is quickly expanding from front-end IT development into business units and becoming an integrated approach to deliver business value across the entire value chain. Digitisation means that companies of all sizes and across all sectors are treating ‘Agile transformation’ as a strategic priority.

In the world of “bits”, the principle of decentralisation is reflected in standardised design patterns that favour small distributed elements in the form of containers, microservices and service meshes to address complexity and optimise for resilience. In fact, we’re so confident of our ability to absorb the unpredictable that we purposely use other tooling to inject “chaos” to probe and proactively fail production systems.

Open source software contribution, responsible for the majority of the world’s software, architectures, languages, systems and progress, operates effectively without positions and promotions. Contributors work in communities on projects fueled by their interests and passions, fostering collaborative problem solving as well as a competition for impact.

Self Regulation Through Site Reliability Engineering (SRE)

The devolution of traditional structures and emergence of new models for decentralised authority has inspired operations approaches like Google’s famed “Site Reliability Engineering” practices. SRE teams focus on creating tools and software services for the other software development engineers to use in self-service models, in order to increase productivity and system stability (with the lofty goal of “automating themselves out of a job”).

The SRE model includes a focus on self-regulation and self-determination based on system stability metrics and “error budgets”. A team is strongly incentivised to create stable working products and tools over having to own and absorb the fall-out of poorly serviceable products. Teams are also not required to stick with an individual project nor continue to collaborate with the same team members. Products and teams can be abandoned if no longer considered viable and worthwhile.

Consequently, bureaucratic tendencies are stifled and effective communication is favoured over traditional models - alerts and service notifications are directed to the right person at the right time who has the ability to resolve the problem.

Founder of Google's Site Reliability team concept, Ben Treynor, is adamant about the importance of execution and empowerment - his first rule is “hire only coders”, i.e. hire those who have the capability to understand their environment and make necessary changes and improvements.

4. Eviscerating Bureaucracy

There’s no manual for uninstalling bureaucracy but several approaches can be explored.

Holacracy (or the Big Bang Approach)

Holacracy is an ambitious, all or nothing, self-management system invented by software engineer Brian Robertson and trumpeted by companies such as Zappos as an answer to old cultural and bureaucratic models. It’s a decentralised, experimental “operating system” where roles are divorced from individuals, no manager constructs and limited hierarchy, intended to give employees more control of their own jobs and remove politics and power plays. It's very interesting and provides a great challenge to the traditional ideologies. While the system is fluid, flexible and encourages creativity and ownership, for larger initiatives, it can be time-consuming and divisive to gain alignment (as we’ve seen with Medium who adopted holacracy in 2013 only to abandon it three years later citing issues with coordination at scale). A better approach might be a more incremental removal of certain bureaucratic features in the organisation, rather than an all encompassing ‘big bang’ approach like Holacracy.

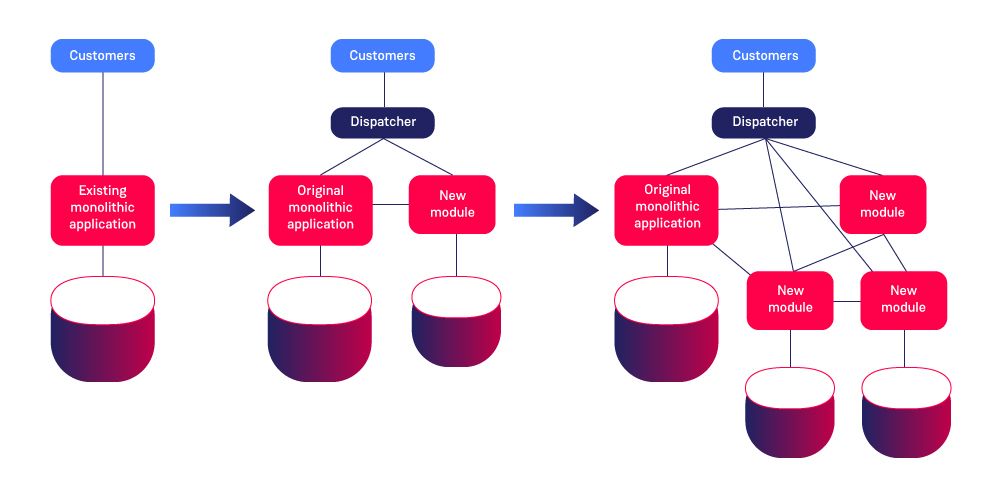

Strangling Bureaucracy Incrementally

Perhaps software design might offer more useful solutions for the challenge of modernising and deconstructing large legacy monolithic systems. Well known approaches like Martin Fowler’s “strangler pattern” advocate incrementally breaking the target legacy system into distributed, decentralised smaller modules. This is achieved in stages by rerouting and redistributing the communication flow. The process completes when the original legacy system is made redundant and easily removable.

Bureaucracy Busting Hackathons

Leading silicon valley firms like Facebook and Netflix have embraced crowd-sourced experimentation in the form of “hackathon” style events over traditional “change management” to tackle operational challenges. The “One Gov Team”, a UK-based digital innovation community focused on the public sector, are running “bureaucracy hacks”. They experiment with 3-5 smaller problems that they feel can be rapidly prototyped in a day, treating each small problem like a layer of red tape to be incrementally stripped away and solved.

Reinvent Organisational Architecture & Ideology

As Prof. Hamel argues, to create game changing innovation and build future-proof and future-worthy organisations, we have to go deep and challenge our foundational beliefs. We start by scrutinising both the architecture and ideology of modern management.

Traditional top-down authority structures perpetuate the past and under value new thinking. Therefore, Hamel says they are profoundly unsuited for enhancing adaptability, innovation or engagement. And deep seated organisational and managerial ideologies based on control, rules and standards may be required but aren’t the only ingredients for success. Hamel notes that freedom and control can co-exist and individuals need freedom to bend the rules, take risks, go around channels, launch experiments and pursue their passions.

5. Pioneering Post-Bureaucratic Organisations

Each organisation is unique and faces a distinct set of challenges that require their own customised approach to uninstalling the malware of bureaucracy. However, a small but growing number of successful post-bureaucratic organisations have developed a variety of models - with common patterns - that prove that complex, global businesses can be run with minimal or no bureaucratic cost.

- Zappos, the US online shoe & clothing retailer, having mostly adopted Holacracy, is now trying to solve the next challenge: finding an alternative to top-down budget allocation so that teams have more freedom to pursue economic ventures.

- French manufacturer, FAVI, employs over 600 people but has no HR department, middle management, time clocks or employee handbooks. Dispensing with central control, they instead created 20 teams, each dedicated to a specific customer who are also responsible for managing their own personnel, product development and purchasing. All teams collaborate as a big community with a common purpose.

- The Vinci Group, a French construction company with 200,000 employees, operations in more than 100 countries and the largest construction company in the world by revenue, operates an ‘inverted pyramid’ model with 3,500 business units that operate like internal entrepreneurs. Employees also own 11% of the company shares and are guided by a common set of cultural values.

- Dutch aged care provider Buurtzorg avoids central control and deploys local teams of up to 12 nurses responsible for 40-60 people in a particular area. Nurses operate with autonomy and much less performance oversight, with teams using their own networks to solve problems.

- Haier, the Chinese consumer electronics giant with 70,000 employees has pioneered a ‘micro enterprise’ model by organising into 2,000 self managed teams that transact with each other like mini companies and compete for resources in an internal marketplace. Every team needs to add enough value to internal or external customers to survive. Entrepreneurs within the microenterprise often become shareholders, which makes them self-employed, self-organised and self-motivated.

- W.L. Gore, Morning Star and Valve created an environment where ad-hoc teams can assemble and dissolve instantly. Individuals ‘sell’ their services to other employees with individual rewards closely tied to performance.

- Svenska Handelsbanken, a Stockholm-based bank with more than 800 branches across Northern Europe and the UK, gives each branch has customer and business responsibility as well as decision-making authority in its local marketplace.

6. The Twelve-Factor Post-Bureaucratic Organisation

To build the successful post-bureaucratic organisations of the future, think about the following strategies:

- Become customer focused - Make reconnecting with the customer a strategic priority, measure success by the quality of customer outcomes or adopt Jeff Bezos’ “Customer Obsession” culture.

- Decentralisation - Move from rigid hierarchies to networks of self-organising teams. Abandon consensus-seeking in favour of individual decision-making sovereignty: “No body is your boss and everyone is your boss”.

- Build a neural information network - Reduce email and focus on real-time and co-located teams for rapid communication where possible.

- Create a culture of “Competition for impact” - Foster competition for impact and value amongst teams, reward those that think “WE” and not “ME”, discourage competition for promotions and position.

- Optimise for speed and resilience - Avoid optimising for efficiency and predictability. Measure everything that affects your customers and productivity.

- Cross-pollination of teams - Use continuous inter-team secondments as a mechanism to drive collaboration, promote trust and destroy silos.

- Adopt a blameless culture - Embrace experimentation, retrospective analysis and learning from failures (while not penalising those who have made them).

- Long-term focus - Shift focus short-term maximisation of shareholder value towards long-term objectives and enduring brand values.

- Innovation ideology - Encourage and reward spontaneous innovation at all levels. Embrace critics, treat new ideas and the questioning of established processes as great learning opportunities.

- Invest in ‘servant leaders’ not heroic leaders - focus on the individuals that help those around them flourish, not the control-focused decision makers.

- Transparency - Enable an open widespread information exchange and transparent decision making.

- Build an “ownership” culture - Align rewards with contribution, rather than with power and position. Position mission over title and promotions. Move to peer review not top-down review.

Who knows. Perhaps if Frederick Taylor were able to look at his model through a 21st century lens, he might have suggested something similar.